Editorial: Burns and the World[1]

Liam McIlvanney

In the spring of 1786, Robert Burns was preparing to venture into in ‘guid, black prent’ as he readied his first book of poems for the press.[2] As a local farmer in his twenties, Burns was an unknown quantity, and so the work was to be published by subscription: prospective buyers would sign up in advance to pay their three shillings. A subscription bill for the volume carried the following declaration:

As the author has not the most distant Mercenary view in Publishing, as soon as so many Subscribers appear as will defray the necessary Expence, the Work will be sent to the Press.

As was often the case when discussing his own work, Burns was being a little disingenuous here. Certainly when the profits rolled in, the poet had a definite ‘Mercenary view’ in mind: he needed the money to emigrate. Nine guineas of his profits from Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect would go to pay his passage to Jamaica.

When Burns booked his passage to the Indies in the summer of 1786, ‘his life was falling apart’.[3] The farm he leased with his brother Gilbert was failing. His girlfriend, Jean Armour, was pregnant. Though Burns mooted marriage, Jean’s horrified parents spurned him as a ‘worthless rake’ and packed Jean off to stay with relatives in Paisley. The kirk, whose ire he had roused through a string of biting anticlerical satires, saw its chance for revenge; the fornicator Burns would have to mount the cutty stool. If ‘the holy beagles, the houghmagandie pack’[4] were snapping at Burns’s heels, they were shortly joined by ‘the merciless legal Pack’ (Letters, I, 145), when Jean’s parents took out a warrant to ensure that Burns stumped up for his unborn offspring.[5] At the same time, the poet had gotten embroiled in another messy love affair, with a servant girl, ‘Highland Mary’ Campbell. Small wonder that when Burns sought a ‘grand cure’ (Letters, I, 39) for his troubles, it was the familiar Caledonian panacea: he would get the hell out. Specifically, he would take a job as an overseer on a West Indian plantation managed by a fellow Ayrshireman, Charles Douglas. As a young man, Burns had watched with envy as his well-to-do friends headed off to make their fortunes in ‘the east or west Indies’ (Letters, I, 136), and Jamaica, where a third of the white population was Scots, would give Burns his chance.[6]

Before he had published a word, then, the man who would be Scotland’s National Bard had decided to leave the country. In the event, though Burns was ‘fix’d as Fate’ (Letters, I, 45) to go, he stayed. Two factors seem decisive here. First, Jean Armour bore him twins, a boy and a girl, and the ‘feelings of a father’ (Letters, I, 58) inclined Burns to stay in Scotland. Second, his book – published on 31st July in an edition of 612 copies – proved a spectacular success. Suddenly the nation’s literati were canvassing ways of keeping ‘this Heaven-taught ploughman’ in Scotland. Instead of sailing for Jamaica, Burns travelled to Edinburgh to prepare a new edition of his poems. And though his removal to the capital was a displacement in some ways comparable to emigration (‘At Edinr. I was in a new world’, Letters, I, 145), Burns stayed in Scotland. The man who so nearly became the laureate of the Scottish Diaspora embarked on his career as ‘Caledonia’s Bard’.

But you don’t have to leave to imagine leaving. Through the spring and summer of 1786, Burns made a lasting mark on Scotland’s literature of emigration. From ‘Lines written on a Bank-note’ (‘For lake o’ thee I leave this much-lov’d shore, / Never perhaps to greet old Scotland more!’, K 106, I, 251) to ‘The Farewell’ (‘What bursting anguish tears my heart’, K 116, I, 272), Burns obsessively pictures himself decamping from ‘old Scotia’. He bids tearful adieus to former sweethearts, Masonic buddies and the Ayrshire landscape: ‘The bursting tears my heart declare, / Farewell, the bonie banks of Ayr!’ (K 122, I, 292). In his songs of this period, the surging billows and raging seas of the Atlantic are rivaled only by the poet’s free-flowing tears. These songs have the self-pitying, lachrymose mood of Burns’s sentimental Jacobite pieces, the mood in which Burns paints himself, in one of his letters, as ‘exil’d, abandon’d, forlorn’ (Letters, I, 44).

But Burns was a poet of many moods, and as well as these tearful valedictions he wrote a ballsy, rollicking poem ‘On a Scotch Bard Gone to the West Indies’ (K 100, I, 238). Here, with the ‘bottle-swagger’ of his verse epistles, Burns imagines how a grieving drinking buddy might describe His Bardship’s departure:

He saw Misfortune’s cauld Nor-West

Lang-mustering up a bitter blast;

A Jillet brak his heart at last,

Ill may she be!

So, took a birth afore the mast,

An’ owre the Sea.

To tremble under Fortune’s cummock,

On scarce a bellyfu’ o’ drummock,

Wi’ his proud, independant stomach,

Could ill agree;

So, row’t his hurdies in a hammock,

An’ owre the Sea.

…

Fareweel, my rhyme-composing billie!

Your native soil was right ill-willie;

But may ye flourish like a lily,

Now bonilie!

I’ll toast you in my hindmost gillie,

Tho’ owre the Sea! (37-48, 55-60)The poem is an example of the old Scots genre of the mock elegy, a genre that dates back to Robert Sempill’s seventeenth-century poem, ‘The Life and Death of Habbie Simpson, the Piper of Kilbarchan’. In choosing this form, Burns is implying not just that death might be the upshot of emigration, either on the hazardous voyage (‘My voyage perhaps there is death in’),[7] or else in the torrid climate of the Indies, but that emigration itself is a variety of death.[8]

Several of these works – ‘On a Scotch Bard’, ‘The Farewell. To the Brethren of St. James’s Lodge, Tarbolton’, ‘From thee, Eliza, I must go’ – feature in Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, so that this volume, the most influential book of poems ever published in Scotland, is in part a book about leaving the country. In the same period, Burns composed a poem on emigration that was too inflammatory to be included in his debut volume – indeed, was not published until 1818, long after the poet’s death. ‘Address of Beelzebub’ (K 108, I, 254) has its origin in a newspaper report describing a meeting of the Highland Society of London, at which the Earl of Breadalbane and Mr Mackenzie of Applecross discussed methods of preventing 500 Glengarry Highlanders from emigrating to ‘the wilds of CANADA, in search of that fantastic thing – LIBERTY’. The speaker of the ‘Address’ is Beelzebub, and he commends the lairds’ infernal plan for keeping the Highlanders in thrall. Allow them to escape to North America, says Beelzebub, and the Highlanders might imbibe the dangerous tenets of the American Revolution and imagine themselves entitled to the rights of human beings:

Faith, you and Applecross were right

To keep the highlan hounds in sight!

I doubt na! they wad bid nae better

Than let than ance out owre the water;

Then up amang they lakes an’ seas

They’ll make what rules an’ laws they please.

Some daring Hancocke, or a Frankline,

May set their HIGHLAN bluid a rankling;

Some Washington again may head them,

Or some MONTGOMERY, fearless, lead them;

Till God knows what may be effected,

When by such HEADS an’ HEARTS directed:

Poor dunghill sons of dirt an’ mire,

May to PATRICIAN RIGHTS ASPIRE…

THEY! An’ be d-mn’d! what right hae they

To Meat, or Sleep, or light o’ day,

Far less to riches, pow’r, or freedom,

But what your lordships PLEASE TO GIE THEM?

(7-20, 27-30)This is the other side of the emigrant coin: emigration, figured not as weary, dispiriting exile, but exhilarating freedom; freedom from the hellish conditions of feudal dependence and degradation, and freedom to shape one’s own personal destiny.

In that summer of 1786, then, Burns gave voice to the two powerful organising myths of the Diaspora: emigration as exile and as liberation. But Burns continued to write about leaving even after he’d resolved to stay, and in December 1788 he sent to Mrs Dunlop a lyric that became the world’s song of parting and the national anthem of the Scottish Diaspora. ‘Auld Lang Syne’ (K 240, I, 443) shows Burns’s genius for adapting and reworking old material. The song existed in various versions, but Burns made three inspired changes. He turned a love song into a song of male friendship; he dropped a stately, stilted English for a homely, heartfelt Scots; and he transformed lofty, abstract references to ‘Faith and Truth’ into poignantly concrete images, nowhere more so than in the third and fourth verses, where great distances of time and space are telescoped in tight quatrains:

We twa hae run about the braes,

And pou’d the gowans fine;

But we’ve wander’d mony a weary fitt,

Sin auld lang syne.

We twa hae paidl’d in the burn,

Frae morning sun till dine;

But seas between us braid hae roar’d,

Sin auld lang syne. (13-20)The force of these lines is apparent, even when the idiom may be unfamiliar. There’s a nicely wry moment in David Copperfield when Mr Micawber affirms that, in their younger days, he and Copperfield have very frequently ‘run about the braes / And pu’d the gowans fine’ in a figurative sense: ‘“I am not exactly aware,” said Mr Micawber, with the old roll in his voice… “what gowans may be, but I have no doubt that Copperfield and myself would frequently have taken a pull at them, if it had been feasible’.[9]

Effectively, then, Burns did become the laureate of the Scottish Diaspora, though a week-long foray into northern England was as far as he ventured from home. His sons, however, and those of his brother Gilbert, would range far and wide. Two of the poet’s sons – Colonel William Nicol Burns and Lieutenant-Colonel James Glencairn Burns – served in India with the East India Company and later retired to Cheltenham. Gilbert’s eldest and youngest sons moved to Ireland, and his fourth emigrated to South America.[10] But it was Thomas, Gilbert’s third son and the poet’s nephew, who ventured farthest, as minister and co-founder of the Scottish settlement of Otago in the South Island of New Zealand. Six decades after Burns was booked to leave from Greenock for Jamaica his nephew embarked from the same port on the Philip Laing, bound for Otago.

An entry in Thomas Burns’s shipboard journal records some of the emigrants’ recreations during the arduous, six-month voyage. (Incidentally, here as elsewhere in the journal, Thomas Burns fails to sound much like a ‘censorious old bigot’, to quote Keith Sinclair’s censorious old phrase.)[11]

Saturday 28th January, 1848

[Q]uite cheering to see the Emigrants all looking so like health and in such good spirits, particularly the children in their boisterous glee exerting limbs and lungs with such lively vigour on deck after their lessons are over... In the evenings on Deck we have songs in which they all join, such as Auld Lang Syne, Banks & Braes of Bonny Doon…[12]

We are entitled to assume, I think, that his uncle’s words would have accrued a special resonance for Thomas Burns and the other emigrants on the Philip Laing: ‘Thou minds me o’ departed joys, / Departed, never to return’; ‘But seas between us braid hae roar’d / Sin auld lang syne’.

What we see, in this vignette of life on the Philip Laing, is a pattern repeated throughout the Scottish Diaspora: the poems and songs of Burns become a tangible link with the Old Country, a ‘symbolic focus for Scottish identity in the colonial diaspora’.[13] As James Currie, the poet’s early editor, puts it, Burns’s verse ‘displays, as it were embalms, the peculiar manners of his country’.[14] Burns documents a Scotland on the cusp of transformation, just before the country was racked by the forces of industrialisation, urbanisation and emigration. By packing Burns’s poems in your emigrant baggage, you were taking the Old Country with you. By celebrating Burns when you reached your destination, you were keeping that connection alive. Dunedin, the chief town of the Otago settlement, was special in this regard because it had the direct family connection with Burns, but even without this, there is every chance that the city would have its Burns statue, its Burnsian place names – Mosgiel [sic], Mount Oliphant, Grants Braes – and its Burns Club dedicated, as its first Secretary put it, to ‘keep[ing] green the best parts in the national character’.[15] When the Dunedin Burns Club was founded in 1891, its motto, perhaps inevitably, was the first line of ‘Auld Lang Syne’.

It was through Burns that many emigrant Scots made sense of their dislocation. The life and poems of Burns are central to the story of the Scottish Diaspora, that massive nineteenth-century exodus from the Highlands and the Lowlands to the New Worlds of North America and Australasia. Between the 1820s and the Second World War, around 2.3 million Scots left the country, a figure that represents over half the natural increase in population over this period.[16] A tradition of Burnsian (or, often sub-Burnsian) verse is shared by most of the major destinations of the Scottish Diaspora. Indeed, some of the traditions of Burnsian verse predate the major nineteenth-century movements of Scots: the corpus of Ulster-Scots poetry, modelled – though not slavishly – on the work of Burns, flourished in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (though we should note that poetry in Scots had been written in the province since at least the 1720s).[17] In the nineteenth century, Canada, the United States, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand all had their Burnsian verse traditions. Many of these writers betray a Burnsian ambivalence towards emigration. John Barr, the ‘Bard of Otago’, could sound the mournful note of exile (‘Thy very name, o Scotia dear, / Brings saut tear to my e’e’),[18] but he wasn’t slow to celebrate his new abode, measuring his current felicity against the squalor and destitution of industrial Scotland:

There’s nae place like Otago yet,

There’s nae wee beggar weans,

Or auld men shivering at our doors,

To beg for scraps or banes.[19]In the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries, many of the ‘Burnsian’ poets of the Scottish Diaspora were undoubtedly poor imitators and pasticheurs. But there were others who, as David Goldie puts it in his article in this issue, developed rather than simply mimicked the Burns tradition. One striking example of a postwar writer whose work develops the Burnsian legacy, and for whom Burns represents a ‘constant presence’ and ‘point of reference’, is New Zealand’s pre-eminent twentieth-century poet, James Keir Baxter.[20]

From the juvenilia to the mature poems, a central element in James K. Baxter’s imaginative mythology was the life and work of Burns. But Baxter’s preoccupation with the Scottish poet seemed, quite naturally, to assume a sharper focus when Baxter returned to his hometown of Dunedin in the mid-1960s to take up the Robert Burns Fellowship at the University of Otago. That New Zealand’s ‘premier literary residency’ should be named after Scotland’s national poet is itself suggestive of the imaginative connections between the two countries. Established in 1958 to commemorate the bicentenary of Burns’s birth the following year, the Robert Burns Fellowship is a year-long position, and provides an office along with a salary equivalent to that of a full-time university lecturer. Its aim is ‘to encourage and promote imaginative New Zealand literature and to associate writers thereof with the University’.[21] When Baxter returned to his hometown of Dunedin in the mid-sixties to take up the Robert Burns Fellowship at the University of Otago, he had, to adapt Hoagy Carmichael, Scotland on his mind. In a public lecture entitled ‘Conversation with an Ancestor’, Baxter traces his whakapapa back to the earliest Scottish settlers of Otago:

I have seen inwardly my first ancestors in this country, those Gaelic-speaking men and women, descending with their bullock drays and baggage to cross the mouth of what is now the Brighton river; near to sunset, when the black and red of the sky intimated a new thing, a radical loss and a radical beginning; and the earth lay before them, for that one moment of history, as a primitive and sacred Bride, unentered and unexploited. Those people, whose bones are in our cemeteries, are the only tribe I know of; and though they were scattered and lost, their unfulfilled intention of charity, peace, and a survival that is more than self-preservation, burns like radium in the cells of my body; and perhaps a fragment of their intention is fulfilled in me, because of my works of art, the poems that are a permanent sign of contradiction in a world where the pound note and the lens of the analytical Western mind are the only things held sacred. I stand, then, as a tribesman left over from the dissolution of the tribes.[22]

It should be clear here that Baxter is mythologising his ancestry, as poets do, and shaping his family past to suit his present purpose as an artist. It’s very clearly a literary vision: ‘the earth lay before them’ echoes the ending of Paradise Lost: ‘The World was all before them, where to choose / Thir place of rest, and Providence thir guide’.[23] But it also echoes that plangent moment in The Great Gatsby, when Nick Carraway imagines the American continent encountered by the first Dutch settlers, when man stood ‘face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder’.[24] Like Nick Carraway, Baxter feels that this pure, originary moment, this ‘radical beginning’, has been soiled by commercialism and materialism. But he views art as a means of reconnecting to that state of social and psychological wholeness which he designates as ‘tribal’.

It’s worth noting that Baxter’s vision of Gaelic-speaking settlers privileges certain elements of his Scottish ancestry over others. The ancestors Baxter mythologises are his paternal grandparents and their kin: McColls and Baxters from Appin and the Isle of Bute, crofters and farmers, Gaelic-speaking Highlanders. He has less use for the Scottish ancestors on his mother’s side, who were equally Scottish, but of a different stamp. Baxter’s maternal grandfather was John Macmillan Brown, a high-achieving product of the academic culture of the Presbyterian Lowlands. Born in Irvine in Ayrshire, a staunch Presbyterian (at one stage he planned to study for the ministry), Macmillan Brown took a first in Mental Science at Glasgow University, was the Snell Exhibitioner at Balliol College in Oxford and became the foundation professor of Classics and English at the University of Canterbury.[25] As Alan Riach points out, Baxter’s enthusiasm for ‘the only tribe’ of the Scottish Gaels may relate to his growing involvement with the ‘other tribe’ of New Zealand Maori:

Privileging the tribal aspect of his family history over the academic, making so much more of his Scottish Gaelic-speaking ancestors than he did of the solid academic tradition that adhered to his mother’s side of the family, was a means by which Baxter could affirm a precedent for his adoption of Maori tribalism.[26]

This is largely true, but it seems to me that Baxter found a means of negotiating and interrogating the divergent aspects of his Scottish inheritance (as well as engaging with Maori), and that he found this in the complex and ambivalent figure of Robert Burns – a Lowlander and a Presbyterian, but one whose anarchic vitality and gleeful anti-Calvinism aligned him to the ‘tribal’ culture that Baxter aimed to celebrate.

In another of the lectures he gave as Robert Burns Fellow, Baxter reflects on what we might call ‘the predicament of the New Zealand writer’ and discusses the challenge of forging a national voice in New Zealand poetry. He argues that the task of New Zealand’s early poets was not to create a national poetry from scratch, starting from some kind of aesthetic Year Zero, but to adapt the forms and modes of English and Scottish poetry:

It would be absurd to imagine that the first poets of a new country have to create new verse forms or an entirely new literary idiom. What happened in America, Australia, and in a lesser degree Canada and South Africa, where English-speaking immigrants or their descendants began writing poetry, was a new amalgamation of borrowed forms, modified idioms and indigenous material.[27]

To demonstrate what this customising of Old World forms might look like, Baxter quotes his own father’s satirical poem, ‘McLeary’s Lament’, in which a local Otago farmer protests against the County Council’s decision to drive a road through his farm:

In all these gullies I’ve made bridges

With great logs split by mall and wedges;

I’ve mown the fern from off the ridges

To make pig-bedding;

And with great care I’ve nurtured hedges

Around my steading.The stanza form, of course, is the Burns Stanza, that deceptively simple, demanding form – a sestet of four tetrameters counterpointed by two dimeters – that challenges the ingenuity of the poet by requiring four ‘a’ rhymes per stanza. It’s a useful stanza for comic verse; it generates a tumbling momentum, broken by the short fourth line in a way that often sets up a wry aside in the final couplet. Baxter comments as follows on his father’s use of the form:

My father’s ear and nose were leading him in the right direction when he borrowed the forms and something of the language of Burns and applied them to the situation of a New Zealand farmer at war with the County Council.

This procedure – borrowing the forms and something of the language of Burns and applying them to New Zealand situations – describes the work of Baxter fils as well as Baxter père. Baxter adopts the Burns stanza (in ‘The Thistle’), deploys the lexis of Burns (‘The Debt’), cultivates Burnsian genres like the verse epistle (‘Letter to Sam Hunt’), borrows Burns’s octosyllabic couplets (‘Letter to Max Harris’), alludes to Burns (‘A Ballad for the Men of Holy Cross’), rewrites Burns (‘Henley Pub’ is a Pig Island version of ‘Tam o’ Shanter’), addresses Burns (‘Letter to Robert Burns’), and ventriloquises Burns (‘A Small Ode on Mixed Flatting’). In its ideation, imagery, technique, form and language Baxter’s poetry shows a deep indebtedness to the work of the Scottish poet.

But the connection between the two poets goes far beyond the transmission of influence. Baxter himself accords Burns a special catalytic significance. Burns was the first poet Baxter encountered, absorbing his work both orally from family recitations and through the printed page. He was introduced to Burns by his father, Archibald Baxter, ‘without whom I would never have come to a knowledge or practice of poetry’.[28] Whether Baxter would have become a poet without the example of Burns must remain a moot point. Certainly, the kind of poet Baxter became – a national bard, a ‘tribal shaman’, a writer of risky erotic verse and political satire, a pastoral poet, an exponent of avowedly popular forms like the ballad and the verse epistle – owes a good deal to the example of Burns. When Baxter wrote of Burns that

He liked to call a spade a spade

And toss among the glum and staid

A poem like a hand grenade– he might have been describing himself.[29] Burns is also, for Baxter, a great ‘tribal’ poet, and his engagement with Burns foreshadows and facilitates Baxter’s engagement with Maori culture and spirituality in the Jerusalem period. When Baxter argues that ‘The Maori is in this country the Elder Brother in poverty and suffering and closeness to Our Lord’,[30] he is echoing Burns’s lines on Robert Fergusson: ‘O thou, my elder brother in Misfortune, / By far my elder brother in the muse’ (K 143, I, 323).[31]

Baxter was more exercised than most holders by what he called ‘the situation of being a Robert Burns Fellow’.[32] Indeed, he regarded the Fellowship ‘more as a hair shirt than a sinecure’.[33] Believing that it is the artist’s duty to criticise the ‘administrative machines which embody and express the mind of Caesar’ (of which the University of Otago is – in Baxter’s view – undoubtedly one), and fearing that a comfortable job – ‘the illusion of material security’ – would be bad for his art, Baxter was nervous about accepting the Fellowship.[34] In the end, he felt able to accept it precisely because it was named for Robert Burns, a poet whose work could inoculate Baxter against the virus of academia:

I could accept it as if from the ironic ghost of Burns (too long loved and too well know for any misunderstanding) and keep in mind his warning against those who try to court the daimon through scholarship:

‘A set o’ dull conceited hashes

Confuse their brains in college classes;

They gang in stirks, and come out asses,

Plain truth to speak;

An’ syne they think to climb Parnassus

By dint o’ Greek…’[35]Having accepted the Burns Fellowship as somehow a gift from Burns, it was hardly surprising that Baxter should devote some of his tenure to exploring his own relationship with the Scottish poet. He did this in a series of talks, some given to the Otago English Department, and later published as The Man on the Horse (1967). The title essay conducts a tour-de-force exposition of the symbolism of Burns’s ‘Tam o’ Shanter’. It also meditates on what Burns has meant for Baxter:

To me, though I write and speak in English, he is much nearer than Shakespeare; and the reason I prefer the ranting dog of Kilmarnock to the swan of Avon is, on the face of it, easy to find. Before I was six years old, I knew Tam o’ Shanter by heart, and portions of other poems by Burns, having received them orally from my father; and when a small white book, the first book of verse I remember seeing, was put into my hands, it was a selection from Burns, a tribal gift, the book by which I could communicate with the dead and myself understand the language of the daimon. It was also a protective talisman. The society into which I had been born – and indeed, modern Western society in general – carried like strychnine in its bones a strong subconscious residue of the doctrines and ethics of Calvinism; and in Burns’s poems the struggle of the natural man against that inhuman crystalline vision of the rigid holiness of the spirit and the total depravity of the flesh was carried out with superb energy, precision and humour.[36]

For Baxter, Burns’s poems provide the antidote to the spiritual and social ‘strychnine’ of Calvinism that the Scottish settlers brought to New Zealand. The active element in Burns’s work, the force that will repel the deadening effects of Calvinism, is, for Baxter, bawdry: ‘Burns is alone among the great post-Reformation poets in his capacity for genuine bawdry’.[37] Through his erotic verse, Burns acts as a ‘kind of tribal shaman’, helping Calvinistic Scotsmen and their Pig Island descendants reconnect with a ‘lost folk heritage’.[38]

Baxter’s vision of Burns as the poet who ‘cracked the wall of Calvin’s jail’[39] was given vivid currency in 1967 when the Burns Fellow intervened in the local dispute over ‘mixed flatting’. The University of Otago had forbidden male and female students from cohabiting, and Baxter weighed into the debate with a poem co-opting the bawdy Burns as the spiritual forbear of the mixed flatters:

King Calvin in his grave will smile

To know we know that man is vile;

But Robert Burns, that sad old rip

From whom I got my Fellowship

Will grunt upon his rain-washed stone

Above the empty Octagon,

And say – ‘O that I had the strength

To slip yon lassie half a length!

Apollo! Venus! Bless my ballocks!

Where are the games, the hugs, the frolics?

Are all you bastards melancholics?

Have you forgotten that your city

Was founded well in bastardry

And half your elders (God be thankit)

Were born the wrong side of the blanket?

You scholars, throw away your books

And learn your songs from lasses’ looks

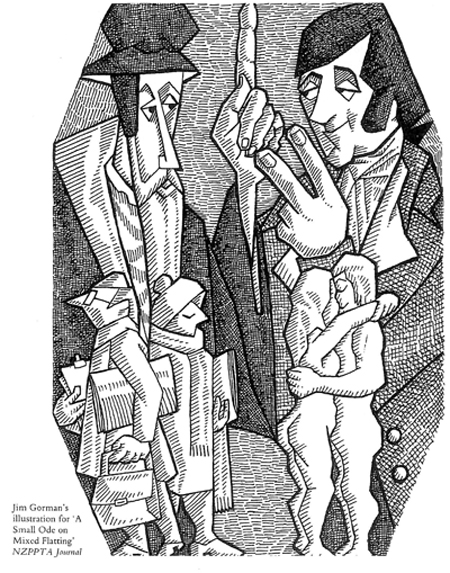

As I did once – ’[40]When Baxter’s ‘Small Ode on Mixed Flatting’ was first published, it carried a ribald illustration by Jim Gorman, in which the vaginal V-sign of Robert Burns confronts the phallic forefinger of John Knox, as the nude mixed flatters face the staid professors.

From W.H. Oliver, James K. Baxter: A Portrait (Wellington: Port Nicholas Press, 1983)

The image nicely dramatises Baxter’s state of mind in this Dunedin period. Baxter took these oppositions seriously. Indeed, even before he took up the Burns Fellowship, Baxter had decided that bawdry was the weapon to wield against Otago’s emasculating academics. He wrote to Kevin Ireland in 1965: ‘The only way to stuff them is to speak bawdy on all occasions, on and off the stage…’.[41] There was, therefore, a talismanic significance to the copy of The Merry Muses of Caledonia, a collection of bawdy songs featuring many by Burns, which was one of the few books Baxter kept on the shelves of his Varsity office.[42] While in Otago, Baxter not only spoke and read but wrote bawdry. The Baxter notebooks in the Hocken Library in Dunedin contain a ‘great quantity’[43] of unpublished erotic poems, many written while Baxter held the Burns Fellowship, and it seems likely that further research will uncover more ‘Burnsian’ bawdry in the Baxter archive.

That bawdry should be one of the bonds between Burns and a poet separated from him by two centuries and twelve thousand miles is hardly surprising. As Jeffrey Skoblow notes in his essay for this issue, the ‘politics of Baudy situates itself underneath all other politics: Scots and English, in fact everyone on earth, all share these lords and devils’. The other essays in this issue of IJSL share Skoblow’s global scope, showing not merely that there is life in Burns Studies beyond the 250th anniversary jamboree in 2009, but that the practice of confining Burns to his Scottish contexts – ‘Scotch drink, Scotch religion, and Scotch manners’ in Matthew Arnold’s dismissive formulation – has been firmly set aside. Gerard Carruthers’ article explores Burns’s ‘slippery relationship to things Irish’, showing how the poet’s Irish allusions represent important ‘portals’ on his poetry. Fiona Stafford discusses the ‘unexpected power of “low” language’ in Burns, and assesses Burns’s significance for his ‘Lancashire follower’, the Victorian dialect poet Samuel Laycock. Gilles Soubigou charts Burns’s catalytic impact on nineteenth-century French art, from the rural ‘manners-painting’ poems that made Jean-Francois Millet ‘wish more ardently than ever to express certain things which belong to my own home, the old home where I used to live’, to the great ‘wild ride’ narrative that inspired Eugène Delacroix’s three versions of Tam o’ Shanter. David Goldie’s thoughtful, wide-ranging study reviews the invocations of Burns in the popular press during the global conflagration of 1914-18, which saw Burns co-opted both as pacifist and militarist, Scottish nationalist and British unionist. With a tighter focus but no less ambition, Alex Watson’s essay interrogates Burns’s glossaries to illuminate the ‘important role paratexts play in negotiating power-relations between different cultures’, suggesting that Burns is ‘not only of importance to Scotland, but to the world’. In her account of the ‘diasporic figure’ of James Currie (also treated in Corey Andrews’s piece), Leith Davis discusses Burns as a ‘global celebrity’. Another global celebrity, Walt Whitman, viewed Burns as a strong precursor, and the links between these ‘bards of democracy’ form the basis of Jeffrey Skoblow’s article. In its own way, each of the essays in this issue of IJSL confirms Skoblow’s contention that, for Burns ‘there is no contradiction between Scotland and the World’. As Ralph Waldo Emerson insisted, Burns’s songs are not Scotland’s alone: ‘They are the property and solace of mankind’.[44]

NOTES

[1] I am grateful to Dr Christine Prentice and Dr Thomas McLean for their comments on an earlier draft of this editorial.

[2] Robert Burns, ‘To J. S****’, The Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, ed. by James Kinsley, 3 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), Poem 79, I, 179. All further references to Burns’s poems and songs will be from the Kinsley edition, abbreviated as ‘K’, and will give poem number as well as volume and page number.

[3] Robert Crawford, The Bard: Robert Burns, A Biography (London: Jonathan Cape, 2009), p. 212.

[4] The Letters of Robert Burns, ed. by J. De Lancey Ferguson, 2nd edn, rev. by G. Ross Roy, 2 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), I, 37. All further references to Burns’s letters will be from this edition, abbreviated as ‘Letters’.

[5] ‘Her parents…got a warrant to incarcerate me in jail till I should find security in my about-to-be Paternal relation’; Robert Burns, letter to Mrs Dunlop, 10th August 1788 (Letters, I, 293).

[6] Crawford, The Bard, p. 205.

[7] ‘Extempore – to Mr Gavin Hamilton’ (K 99, I, 237).

[8] Compare Thomas Pringle, who in his poem ‘On Parting with a Friend Going Abroad’ envisions a boatful of emigrants as ‘parting spirits’ who ‘look to earth once more… / From the dim Ocean of Eternity!’; Thomas Pringle: His Life, Times, and Poems, ed. by William Hay (Cape Town: J. C. Juta, 1912), p. 161.

[9] Charles Dickens, David Copperfield, ed. by Jeremy Tambling (London: Penguin, 1996), pp. 387-8.

[10] Ernest Northcroft Merrington, A Great Coloniser: The Rev. Dr. Thomas Burns, Pioneer Minister of Otago and Nephew of the Poet (Dunedin, NZ: The Otago Daily Times and Witness Newspapers Co., Ltd, 1929), p. 35.

[11] Keith Sinclair, A History of New Zealand (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1959), p. 90.

[12] Transcript of Journal of Rev. Thomas Burns on the ‘Philip Laing’, Hocken MS – 440/18.

[13] Nigel Leask, ‘Scotland’s Literature of Empire and Emigration, 1707-1918’, in The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature, Volume 2: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire (1707-1918), ed. by Ian Brown, Thomas Owen Clancy, Susan Manning and Murray Pittock (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), pp. 153-62 (p. 157).

[14] James Currie, The Works of Robert Burns with an Account of his Life and a Criticism on his Writings to which are Prefixed Some Observations on the Character and Condition of the Scottish Peasantry, 8th edn, 4 vols (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1820), I, 31-2.

[15] William Brown, letter to the Hon. Sec. of the Bathurst Branch of the Highland Society of New South Wales, 6 July 1892, Letterbook of Dunedin Burns Club, Hocken MS – 2047.

[16] T. M. Devine, ‘Introduction: The Paradox of Scottish Emigration’, in Scottish Emigration and Scottish Society: Proceedings of the Scottish Historical Studies Seminar, University of Strathclyde, 1990-91, ed. by T. M. Devine (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1992), pp. 1-15 (pp. 1-2).

[17] Liam McIlvanney, ‘Across the Narrow Sea: The Language, Literature and Politics of Ulster Scots’, in Ireland and Scotland: Culture and Society, 1700-2000, ed. by Liam McIlvanney and Ray Ryan (Dublin: Four Courts, 2005), pp. 203-26. See also Revising Robert Burns and Ulster: Literature, Religion and Politics, c. 1770-1920, ed. by Frank Ferguson and Andrew R. Holmes (Dublin: Four Courts, 2009), reviewed by Gavin Falconer in this issue.

[18] John Barr, ‘The Yellow Broom’, Poems and Songs, Descriptive and Satirical (Edinburgh: John Grieg & Sons, 1861), p. 83.

[19] John Barr, ‘There’s Nae Place Like Otago Yet’, Poems and Songs, p. 62. Alan Riach traces New Zealand’s Burnsian verse tradition in ‘Heather and Fern: The Burns Effect in New Zealand Verse’, in The Heather and the Fern: Scottish Migration and New Zealand Settlement, ed. by Tom Brooking and Jennie Coleman (Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 2003), pp. 153-71.

[20] Dougal McNeill, ‘Baxter’s Burns’, ka mate ka ora: a New Zealand journal of poetry and poetics, 8 (2009), www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/kmko/08/ka_mate08_mcneill.asp

[21] Nurse to the Imagination: 50 Years of the Robert Burns Fellowship, ed. by Lawrence Jones (Dunedin, NZ: Otago University Press, 2008)

22 [22] James K. Baxter, ‘Conversation with an Ancestor’, The Man on the Horse (Dunedin: University of Otago Press, 1967), p. 12.

[23] John Milton, Complete Poems and Major Prose, ed. by Merritt Y. Hughes (Indianapolis: Odyssey Press, 1957), p. 469.

[24] F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby, ed. by Ruth Prigozy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 143. In his reference to his people’s ‘bones’ being ‘scattered and lost’, Baxter is also, of course, echoing Ezekiel 37.

[25] Cherry Hankin, ‘Brown, John Macmillan 1845-1935’, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, updated 22 June 2007, www.dnzb.govt.nz/dnzb.

[26] Alan Riach, ‘James K. Baxter and the Dialect of the Tribe’, in Opening the Book: Essays on New Zealand Writing, ed. by Mark Williams and Michele Leggot (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1995), pp. 105-22 (p. 120).

[27] James K. Baxter, ‘The Innovators’, Hocken MS – 0739/009.

[28] Baxter, ‘The Man on the Horse’, The Man on the Horse, p. 91.

[29] James K. Baxter, ‘A Small Ode on Mixed Flatting, Elicited by the decision of the Otago University authorities to forbid this practice among students’, The Collected Poems of James K. Baxter, rev. edn, ed. by John Weir (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1981), p. 397.

[30] Frank McKay, The Life of James K. Baxter (Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 237.

[31] On Baxter’s engagement with Maori culture and spirituality, see John Newton, The Double Rainbow: James K. Baxter, Ngati Hau and the Jerusalem Commune (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2009), and John Dennison, ‘Ko Te Pakeha Te Teina: Baxter’s Cross-Cultural Poetry’, Journal of New Zealand Literature, 23.2 (2005), 36-46.

[32] Baxter, ‘Conversation with an Ancestor’, The Man on the Horse, p. 11.

[33] James K. Baxter, ‘Conversation with an Ancestor’ (‘A’ Draft), Hocken Library, MS – 0739/006, p. 1.

[34] ‘Conversation with an Ancestor’ (‘A’ Draft), Hocken Library MS – 0739/006.

[35] Baxter, ‘The Man on the Horse’, pp. 92-3.

[36] Baxter, ‘The Man on the Horse’, Hocken MS – 0739/013. I quote here from the typescript in the Hocken Library. In the published version – see The Man on the Horse, p. 92 – Baxter modifies the final sentence to have Burns struggling against the ‘rigid holiness of the elect’ (my emphasis), indicating that his target here is doctrinaire Calvinism rather than Christian spirituality.

[37] Baxter, ‘The Man on the Horse’, The Man on the Horse, p. 96.

[38] Ibid., p. 97.

[39] Baxter, ‘Letter to Robert Burns’, Collected Poems, p. 290.

[40] James K. Baxter, ‘A Small Ode on Mixed Flatting’, Collected Poems, p. 397.

[41] Letter to Kevin Ireland, 26 October 1965, Alexander Turnbull Library MS 2587, quoted in W.H. Oliver, James K. Baxter: A Portrait (Wellington: Port Nicholson Press, 1983), p. 103. Oliver observes that Baxter ‘quite seriously believed in the magical effect of obscene words’ (p. 104).

[42] McKay, p. 209.

[43] Oliver, James K. Baxter: A Portrait, p. 104.

[44] The Centenary Edition of the Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 12 vols, ed. by E. W. Emerson (Boston and New York, 1911), XI, 440-3; reprinted in Robert Burns: The Critical Heritage, ed. by Donald A. Low (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974), p. 436.